What are some of your favorite tunnels in the world?

Month: April 2014

Rohrschach Moves III

Waves undulate below my bare feet

Content on the griddle-like metal deck

Prow lunging me through the lapis and emerald green liquid

Towards my heart’s desire and dream

Salt-taste delicious upon my full, parted lips

Darkest of sun glasses perched upon the sharp bridge of my nose

Jutting defiantly towards the turquoise sky inhaling the liberating spray

Waves undulate between heart and throat

Engulf these byways with torrential tears and stifling sobs of wonderment

For freedom is mine, no return ticket in my snug pocket

I am a water-birth and the way remains mine, confirmed by decades of self-denial

Close only counts in horse-shoes

This life will be mine

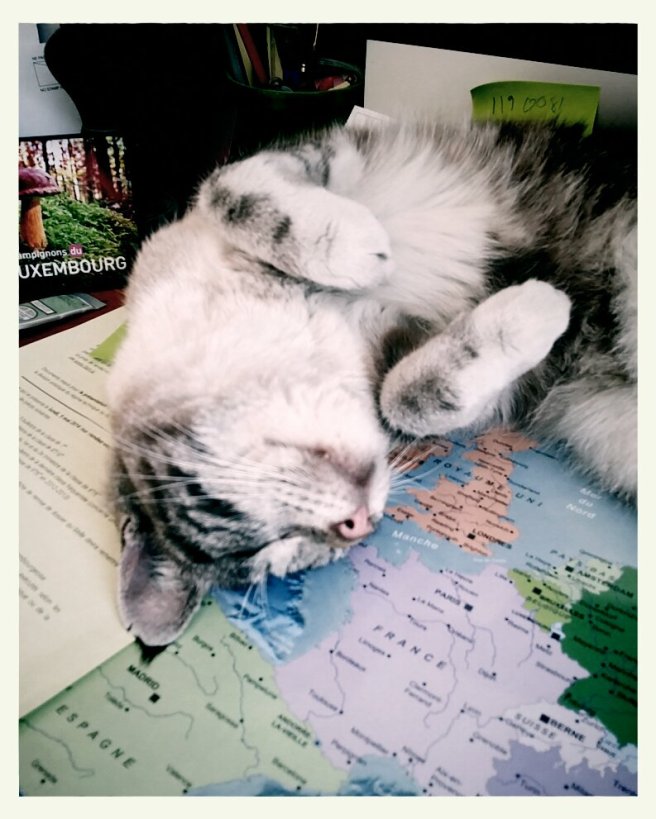

The Cat who conquered the World

Spring sprung out of Bounds

Yesterday I had 1001 errands to run downtown. At first, I was just glad that it wasn’t raining. But my perception picked up speed once I was on my way from the parking lot to the city center. I pinched myself at the beauty and the fact that I feel so fortunate to live in such a gorgeous, green city. All of a sudden, my errands didn’t seem so pressing and important. Dragging my feet to stop and smell the proverbial roses along the way made up for the so-called lost time. The grassy clearing offered the passers-by colorful carpets of tulips and buttercups and the sun filtering itself through the freshly coiffed tree crowns evoked ethereal tunes in my ears. The resident orchestra always on-call in my brain whispered strains of Debussy. I am at my best when this happens to me; in flow on my slow-motion trek through the municipal park. For tomorrow, I have decided to pay a visit to the Villa Vauban museum. The grounds, with their exquisite flowerbeds, beckon with comfortable chairs and benches. No mistake about it, I hear my very own name carried by the suave springtime breeze. Bliss.

A Prodigal Daughter’s Journey

I have traveled more than I can remember since I turned 18. Couldn’t wait to move on with my life, see the world outside of my neighborhood. I had run away from the crap that ate away at me. Things I could never assign a name to. Europe and more Europe. I did it. I have not stopped. It was in Europe where I married, worked and gave birth to my children. Only recently am I able to call my adoptive country my true home. I discovered this through living within the juxtaposition of loss and life. I do not claim to have all of the answers to my questions. But I do understand that I must ask them and act accordingly. My father’s death set my journey in motion and gave me the gift of courage to be true to myself.

I always yearned to leave and being scared shitless didn’t stop me. My late father shared his “Wanderlust” with me. He was drafted into the military in 1942; a strapping blond farm boy from the Missouri boot heel, wanting nothing more than to venture out and discover the heady world of the newsreels. Those who knew him opined that he wanted to conquer the world in a gentle way, go dancing at the Waldorf Astoria hotel, swinging to the tunes of Tommy Dorsey’s Band with a pretty girl on his arm. They didn’t know him as I did. He went willingly to serve his country, but there were two other reasons for his journey to the induction center. One being the obligation he had to his mother still living “down home” on the small family farm and his brother, who ran the farm single-handedly. The military service meant a steady pay envelope. Regularly, he sent money to the folks back at home. His brother had flat feet, so the war making left my dad’s older brother in peace. The young man from the Show-Me-State, who would mature into my father twenty and some years later, kept the second reason close to his heart, like a hot hand of cards in a poker game. He went for the beauty of the sea and to play baseball. This is how I see it and his choice of reminiscing vocabulary gave credence to my spin on it. As a teenager, he had played for the St Louis Cardinal Farm Club and excelled at first base and as shortstop. Upon finishing his basic military training at the CCC* camp in Farragut, Idaho he was sent to New York to board his ship, a destroyer escort, called the USS Daniel 335. From New York my father sailed off with his shipmates on what the Navy calls a “shakedown cruise”, a testing of the waters up and down the eastern seaboard of the United States and the seaworthiness of the fresh basic training graduates. Checking gauges and pistons, engines and diesel fuel. My father was a motor machinist’s mate with aplomb. There was nothing that he couldn’t fix if needed. He always spoke with nostalgic fondness of his engine room and fellow sailors and imitated the various noises to illustrate his oral recollections.

My father unfolded this story to my siblings and me a million times and we loved it. These were the happy and carefree days before his daily sailor’s existence became fraught with the dangers of the Nazi U-Boots marauding throughout the North Atlantic. Once this lucky warship docked in Guantanamo Bay, the sailors delighted in a long stretch of nothing but rest and recreation. I am sure they had to muster up from time to time, but my father never mentioned that mundane detail of a military man’s life. It was baseball and nothing but baseball. I always wondered why the US Navy took a boatload of sailors so far down the coast and let them loose to play baseball under the hot Cuban sun. It was wartime, after all. I wondered that as a ten-year old little girl hanging onto every word of my father’s story yet I never thought of asking him about it. I think I know the answer: Fun before the perils arrived. The progression of the story never varied. A good night’s sleep out of doors in a tent because the heat in the barracks during the night would have been more than a shipload of sweaty sailors could take on a sweltering Caribbean night. The breeze from the water would caress exposed toes and pass up the body to cool the sweaty brow. My father spoke in vivid images. He took in the simple, ethereal sorts of sensations, omnipresent, but unnoticed by most. This is how he was able to get along with man and beast. His nature was gentle and intuitive, gently strung, ponderous. Whenever he told his war stories, they were never about battles, but of the human condition and personal engagement. As he aged, the same stories took on a deeper, more poignant meaning than the first 5, 10, or twenty times he told them. Towards the end of his life this was the case more often, I surmise. As he lay dying in his 83rd year, I still wondered if he found himself back on his ship feeling free as a bird in his youth. I like to imagine it so. If he did, his buddies would have been present and glad of his presence. His children would not have been born yet, but were in his hidden and most intimate of thoughts. Weaving my siblings into this story won’t happen. They had their own stories with our father and I cannot touch upon that. In the pecking order my place was the lofty position of first-born daughter after the arrival of five sons. Had my mother been in any kind of conscious shape at my birth I would have come into this world with a different name, but when the nurses asked my father what I would be called, he stepped up and promptly named me after his favorite actress, Yvonne De Carlo, of Lily Munster fame. This is fine with me because my dad was the coolest guy in the world. At his funeral, a friend elegized him a true buddy to everyone who knew him. He was my hero, and then later my grief and loss- measuring-stick. Whatever one chooses to call it. I never know when a new gust will shake me up. And I doubt that I am alone on this count. It means that I have not forgotten. I need my memories just as my lungs need oxygen.

In the first months and years I didn’t get a handle on my grief like my siblings seemed to have done. Everyone is different. I functioned in public as if nothing had changed in my life. But in private I was in a shambles. The wound is just as fresh as I write this, but I do change the bandage on it as necessary. As much as this sounds crazy, my father’s passing provided me with a new level of strength to make some necessary changes in my life. Recently I explained to a close friend that my father’s death allowed me to go on and attack the biggest problem of my adult life: my un-marriage. It sounds weird, I know. I spent years lamenting to him about the dysfunction and horror of my married life. He listened and asked me if he could do anything for me. I always said, “No, Daddy, I’ll figure it out somehow”. He would sigh and we would talk a while longer, hang up the phone and go about our lives. I did begin making decisions after my father’s death just as soon as I unearthed myself from the first years of grief and despondent existence between these two worlds. Once I got the ball rolling, it never stopped. The torpor and inertia had been conquered. Death of a loved one overwhelms the heart and though process. Time will pass, but the scab gets hung up on things and breaks open when you least expect it to. His passing forced me to confront the hard decisions. My metaphysical safety net disintegrated with his death and with this came a visceral need to build a monument for my dad so that I always had a place where I could leave flowers for him. He taught me to use tools and mix cement after all, so I figured that I could erect anything. But in fact, I planted a majestic King Crimson maple tree in my back yard. He also shared his green thunb with me.

My former grief counselor recommended that I relocate my father. But how does one put such a theory into practice? This sounded like time machine stuff to me. All I could think of was the movie “Back to the Future” and a stainless steel De Lorean car. Indeed it appealed to me because I felt that he was wafting through the ether checking up on me but not being able to help me except through my memories of him. Paradoxically, it was exactly his memory that I often could not bear. Like listening to a song and having the radio go dead before the final verse or catching a whiff of a scent and having the olfactory memory spin in place in attempt to deliver the memory to which the scent is attached. Everyone from the new neighbor lady to the cashiers at his favorite grocery store found him charming, endearing and so kind. He knew them all by name. So it wasn’t just me hanging on. Honestly I hadn’t the slightest idea how to re-locate a spirit over whom I had no control. Time. Time does not heal all wounds. Time gives one ample opportunity to reflect and protect the wounds, that’s all. The wounds never leave.

At the end of a particular session, my grief counselor broke the news that she would be on vacation for 2 weeks. That was back in the days when I attended weekly grief counseling. The alarm bells vibrated noticeably in a deep recess of my central nervous system. “So, where are you going, or is this a “stay-cation” for you?” Small talk followed by a dark feeling of impending doom. “Well, I am actually flying to Cuba with my sister for a break.” At the mention of Cuba I zoned out on her and left her office with a “Have a great time!” As I tumbled down the staircase out into the open air, I thought to myself “Hell’s Bells, Irene is going to Cuba. I wonder if she will be near Guantanamo Bay…?” The next day was spent obsessing and puttering about my house in a dense cloud of distraction. I had an idea that I thought would bring me a bit closer to re-locating my dad but it remained a touchy, uncertain subject. It was logical to me to ask for her help. I have had to learn how to ask for assistance and now felt capable of putting the theory into practice. She had always reminded to let her know if there was ever anything she could be of help with. Cuba materialized into that necessary something. All of the nostalgic stories my dad told about his salad days and the affection he never lost for the months he spent playing his favorite sport on lush baseball diamonds during his World War Two naval service came to me in a torrent. What did I have to lose?

I had loads of unfinished business with my father. I felt that I owed him an explanation for lots of things. I have never really been able to purge my heart of this feeling. Since I left home for good at the age of 18, my father and I exchanged letters regularly. He always made sure to adorn the envelopes destined for his wayward daughter with the stamps from the current philately collection. He was always attentive to detail, especially if it would cause the receiver to feel special or cherished. Thus, it seemed completely logical that a missive written on fine paper with tidy handwriting seemed the only way to go, even in the emotional space around death. This would offer my bruised heart a brief respite from the self-recriminations and maybe stop me from being ever so hard on myself.With that brief letter I intended to “re-locate” my father, or perhaps just a tiny portion of the great loss stuck to his absence. This Grief does define me. It keeps me going in directions I have neglected for so many years. Doing something in a loved one’s memory allows us to hold on to the parts which we cannot and do not wish to let go. I still do not have the “afterlife” conundrum figured out. Who does? This ineffable unknown demands to be dealt with in any way possible I can and shows me that I am on course in the correct direction.

At the office I ducked into one of the private telephone areas and called Irene. Fortunately, her client was late which gave me a few undisturbed minutes to ask her for a favor. I stammered like someone about to ask to borrow a great sum of cash, or to co-sign on a car loan. She said, “yes” in the space of a heartbeat and we made plans for me to drop by her house and hand over the letter. I managed to fit my handwritten letter on one sheet of fine, heavy velum stationery paper, but getting it into a bottle proved a more delicate undertaking. It wasn’t working. Irene told me that she would take care of the bottle once she was in Cuba. I should not worry about it at all. Before leaving I dug a baseball from my purse. The leather smelled good and was both cool and warm to the touch. In a suspended state of agony, I pressed the baseball into Irene’ s hand, hugged her with gratitude, and drove home with a thudding heart and ringing ears.

Irene returned two weeks later and phoned me to schedule my next appointment. I took the afternoon off because I was not sure that returning to the office after my session would be a wise move on my part. I squeezed my car into the last parking space on a bridge and took an additional five minutes to reach Irene’ s office. I was torn between not wanting to delve into my grief issue, yet needing to do so all the same. Hearing the undulating flow of the Alzette below my feet helped calm the sharp nausea playing for my attention. I was not afraid of going into the depths of my session, just of coming unglued. The recovery time usually took days. Irene was to tell me about Cuba.

She met me at the door with a tight hug and big expectant eyes. She is Greek and as such very warm and hospitable. I took my usual seat on the little couch. A cup of hot mint tea was waiting for me on the coffee table. Silence. I kept my impatience at bay. I heard the thud of my heartbeat in my ears. Without a word, Irene reached inside of a drawer, removed a small, clear glass bottle and placed it on the table in front of me. “This is a bottle from the Greek island, Amorgos. People there get the bottles at the Monastery of the Panagia Hozoviotissa** put messages in them and set them adrift in the sea in memory of their loved ones. Dead or in need, she did not specify. My ears became all hot and my bowels cramped up the second I realized that Irene put my letter into such a bottle, so fraught with symbolism. Irene held my hand as she recounted the story of my letter and Cuba. Afterwards we sat in silence. She had somehow managed to thread my short, but bulky letter into the bottle and even had the foresight to bring along a stick of red sealing wax to protect its contents once seaborne. Travel: From Amorgos to Cuba via Luxembourg. A symbolic surrogate burial at sea: Extraordinary measures for an extraordinary man. I had asked Irene to pitch the baseball out into the Caribbean Sea and the message in its bottle should just be sent off on its journey in the most gentle of ways. Irene looked at her hands and hesitated before she spoke. On her exhale she told me that she had read the letter before consigning it to the bottle forever, but not to the end because it had made her cry. I assured her that I was glad that she did read it. A witness made my action all the more real and forced it from the realm of lofty and unfulfilled intentions. After all, in her capacity as my counselor, she was in great part responsible that I was now able to take a step into this unknown abyss of thick, jagged emotions. There was more to her narrative. Instead of simply tossing the two items into the sea, she arranged to have a diver from the scuba diving school at her resort to take her as far out from the Cuban shore into the Caribbean as was safe. With a prayer, she said, the bottle was set afloat followed by the baseball. With a wood-burning iron, I had branded my father’s name and the name of the ship on which his served from 1942 to 1945 into the smooth part of the ball between the red seams. Silence again. Despite the high emotions at hand, I did not break down and sob. I did enough of that at home. But I felt such relief at having gone through with my surrogate memorial idea and so thankful that Irene understood the importance of this gesture. Her generosity of spirit still floors me. The extra measure I chose to honor my father and travel a few miles further on the road of grief partially filled up a deep void which I had been trying to ignore. Grief is a surreal state because it enhances the memory in an unnatural way. I have total recall of my father’s last three days on his deathbed. Just as I am able to recall memories from ages three to five in detail. I still see the arrangement of the big living room that served as his death chamber. We rented a hospital bed to assure his comfort as much as possible as his end neared. 20 years earlier he had established a living will and reminded all of us from time to time of its existence and preeminence: No tubes, no machines. No arguing. We aimed to respect his wishes. For once, my numerous siblings were united, no jealousy, no pulling rank. His three eldest granddaughters were also present. We were united in making it possible for our father to pass from this world to the next in the cocoon and intimacy of his own home. No hospital care, just my siblings, his adult granddaughters and I.

My plane landed at the Detroit Metropolitan Airport on a February 12. The crew on the Lufthansa flight prepped me for what I would soon face. They must have been briefed in Frankfurt about my tearful state and my passage on a compassionate ticket. The memory of the delicate care afforded me by a steward during the near 8-hour flight still causes me to shake my head in gratitude. He shared the name of a fourteenth-century Italian poet. This couldn’t have been a coincidence and I immediately considered him to be my guardian angel of sorts. A spontaneously offered extra blanket and pillow, a warm smile whenever he passed by my seat showed me that he was concerned about me. At one point during the flight, after dinner, if I recall correctly, I lost my composure, not doubt due to the large quantity of red wine I had consumed, and sobbed into my pillow. I was beside myself in this pre-death horror. I remember silently keening, “What am I going to do? What am I going to do?” My mind raced on overdrive. I feared that my dad would die before I had a chance to see his face and hold his hand one more time.

Also traveling to Detroit was a group from India. They sat behind me and to my right in the middle section of the plane. My meltdown had them worried and at one point the Indian lady across the aisle pushed the service bell to summon the steward. I heard her whispering to him about the weeping lady across the aisle. I wanted to apologize, but to look over in her direction would have been the end of me, I felt. My guardian angel swept back into the galley and returned with a small plastic glass containing a clear, syrupy liquid. He must have remembered my choice of after-dinner digestive. Kneeling down in the aisle facing me, he gently pried the pillow from my grasp and put the double shot of Cointreau in my hand. He stayed with me until I downed the thick drops of mercy. Before getting back to his duties, he said, “I am very sorry. This will help you sleep if you will just close your eyes. I’ll check up on you later, but if you need anything, just ring for me.” He re-positioned my blanket and pillow, smiled at me and gently squeezed my folded hands before walking down the aisle to see to another passenger. I slept for a couple of hours, but was glad that I was allowed a big glass of red wine and a refill with the snack before the final descent. I should have been drunk off my ass by then, but the insidious apprehension moved into my brain and converted inebriation into functional numbness.

My brother had sent a close friend of the family to pick me up from the airport. He had also given her a couple of unnamed pills for me. Something strong to keep me doing whatever it was that he was sure I would do, or perhaps not do. A nice thought, but I still had a substantial buzz from all of the in-flight alcohol. I still am not able to share the three days of agony on paper. I am on stand-by for this leg of the journey. I am still not sure what I should pack in my metaphysical suitcase, nor for how many days.

I remember seeing death vigils in films, but I never imagined that I would one day keep one myself. During the three days he lay dying, I never left my father’s side except to use the toilet. My old room was available but remained uninhabited. Timeless hours of coffee and half-eaten donuts marked the acute awareness of my dad’s labored breathing. We ate no more meals except maybe an occasional take-out from Arby’s. A hospice nurse came by to check on my dad a couple times each day. I hated the way she would feel the temperature of his cooling feet and inform us “this is one of the first signs of the end”. “No shit, Sherlock”, I felt like saying. My niece, the registered nurse, briefed the hospice lady on her grandfather’s condition and took over the nursing part once the hospice nurse left for her next patient. We didn’t need her, but she was required by law to check in since my father was registered with the local police as a hospice patient and there was a substantial amount of morphine in the house.

The rest of these three days are surreal with the coming and going of in-laws and a few family friends. My stupor left me speechless. I was glad that the living room was empty of all talking during the night. There was just my sister on the couch and me at my father’s side holding his soft hand. I was relieved that he had managed to stay out of the coma until I arrived home. The three hours we had before the coma claimed him for good are beyond precious to my memory.

On the afternoon of the third day I noticed the death rattle creeping into his breathing already be-labored from the coma sucking him away. The experts say that the sense of hearing is the last to go when a person is dying. I knew this instinctively so, I whispered softly into his ear, or into the blanket covering his now skinny arms. I know that he heard me on his last morning in this dimension. I reassured him that I had come home again and was sorry that I took so long even though had just been home just six months before for my brother’s wedding. I gazed at him and noticed a tear trickling down the right side of his face. Slowly, I rose from my chair and kissed that last tear away and then ran away into the back bedroom and bawled the desperation from the rent in my heart. From the kitchen I heard someone order my brother to go to me. “She is too loud; your father will hear her!” Absurd! He was supposed to hear my keening. I could always talk to him, so hearing my heartbreak would not surprise him. These were the only means I had at my disposal to express the depth of my despair, the only way to show my grief and my deep filial love. Like the math teacher tells you during a test, ”be sure and show your work!” I was sure that I would implode or lose my sanity had I kept my anguish bottled up. I would have run away from this moment.

My father died on a February 15th. The ensuing days still retain their blurred and surreal quality. We only called the hospice nurse an hour or so after he breathed his last breath. My siblings and I needed time to be alone with him, to say goodbye. After we gained our collective composure, the gravity of the situation kicked in. The hospice nurse duly notified the police, who sent a squad car and two officers over to confirm that there was a natural death in the house. They accorded my dad’s dead body a cursory glance and returned to the kitchen awaiting the arrival of the hospice nurse. She was required to dump all the remaining morphine down the toilet in the presence of the two police officers. The night of his death was spent in a funk of disbelief and sleeplessness and for the first few months thereafter I spent my nights in a chair with all of the lights burning. To this day, February is a tainted month.

After his honorable discharge from the U.S. Navy in 1946 my father never permanently returned to the boot-heel of Missouri. Like many of the young men at that time, he traveled North where there were immediate jobs. He would often tell us children how he cussed the cold Michigan winters and was vehement about his aversion to the thought of being buried in that cold northern ground when the time came. But when that sad day did come, we arranged with the director of the Funeral Home to obtain permission to take our dad back down home ourselves. One of my brothers had a brand new van in which the casket fit like a glove. There was no way we could conceive of calling upon the funeral home to take care of the transport for us. We, his children, were one voice in honoring the promise not to bury our Dad in any other place but his home ground. The day after the funeral our convoy of five cars containing brothers, sisters, grandchildren and in-laws set out on my dad’s final voyage. After 60 years he was finally returning to his beloved Missouri. He had really come full turn, he would say. I can here him make an assessment with a certain degree of awe and humility in his voice: “Can you imagine? The sights I have seen in my life? It seems like just yesterday I was on my ship and I made it back alive! Now I am going back home. You know, I was the first groundskeeper at the cemetery when I was just 13 years old and big for my age. I sure would like to be buried next to mom and dad when the time comes.” It is a comfort to still have his voice and speech pattern in my ears, and his unique pronunciation of certain words. The actual burial remains a rough patch for me. But one detail I can commit to paper is that he was interred with the military honors due to him. A Navy honor guard had traveled down from St. Louis for the graveside interment service. Two very pretty U. S. Navy liaison officers accompanied them and took time for the bereaved family members. The presence of two pretty female sailors at his funeral would have caused my dad to smile. I tried to tell them that, but I could not get around the tears choking off my voice. The hug they gave me before leaving made a big difference.

I make it a point to take the anniversary of my dad’s death off from work every year. The first two anniversaries were particularly rough. They are still are, but I am more in-tuned with the emotions nowadays. On this anniversary I make sure to do something for myself. I honor my father this way. I can still hear the way he would say, “I just want you children to be happy, just happy.” I am working on this “being happy” experiment. I listen to the lesson learned and travel regularly in time so as not to forget the hard-won lesson.

Why the message in a bottle? The baseball? My idea was a spontaneous knee-jerk manifestation of a deep need. I had to act in order to go on with my life and attempt to assuage the sharp sense of loss as much as possible. Perhaps my action would notch down the flame of the fire of guilt I felt for having lived overseas for twenty years. I could not visit as often as I would have wanted to due to the dysfunction of my un-marriage. I returned the prodigal daughter. My travels go on: A voyage of the memory. Grief is travel between the then, the now and the beyond. A meeting place for a future time, I hope.

*Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) was a public work relief program that operated from 1933 to 1942 in the United States for unemployed, unmarried men from relief families, ages 18–25 as part of the New Deal. Robert Fechner was the head of the agency. It was a major part of President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal that provided manual labor jobs related to the conservation and development of natural resources in rural lands owned by federal, state and local governments. The CCC was designed to provide jobs for young men, to relieve families who had difficulty finding jobs during the Great Depression in the United States while at the same time implementing a general natural resource conservation program in every state and territory. Maximum enrollment at any one time was 300,000; in nine years 3 million young men participated in the CCC, which provided them with shelter, clothing, and food, together with a small wage of $30 a month ($25 of which had to be sent home to their families). Source: Wikipedia

**Monastery of the Grace of the Virgin Mary, Amorgos, Greece.

Yvonne Koechig, Luxembourg- April 2014. To be continued.